Doctor Who is BACK and I am so excited! I swear I wasn’t intentionally sitting on my Doctor Who reviews for Season 1 to drop on Disney+. Let’s just say I could really use a real-life TARDIS and leave it at that. Quite frankly, I want to take a page out of Ncuti Gatwa’s book: in an interview, he called this The Doctor’s “healing era.” SPOILER WARNING if you reading this review for Doctor Who The RolePlaying Game, and are somehow not aware of how the 15th Doctor arrived on the scene, you can jump ahead a bit…

.

.

.

Are we all still here? Great. So, as you know the 14th Doctor didn’t “regenerate”, he “bi-generated” by splitting in two like an amoeba in a sort of macro-mitosis. (The amoeba description isn’t terribly accurate and I’m not sure macro-mitosis is even a real word. But I swear I went down a rabbit hole I wasn’t expecting and no matter what the scientific topic may be, if you don’t have some higher-level scientific education you’re probably wrong and probably made something up. But anywho…) Two lines in The Giggle truly exemplify this new era. First 15 tells 14 “We’re Time Lords. We’re doing rehab out of order” then later in the episode 14 muses “Funny thing is, I fought all those battles for all those years, and now I know what for: This. I’ve never been so happy in my life.” David Tennant’s 14th Doctor is finally relaxing and enjoying life, while Ncuti Gatwa’s 15th Doctor is the happiest and most playful I’ve seen the Doctor since Tom Baker. He’s accepted and taken responsibility for his actions in the Time War, allowing him to set aside the guilt that has dragged him down across his past 9 regenerations. We, the viewing audience, are left with a season that has been mostly lighter in tone, but that still has a complex and very dark undercurrent for those that want to look at it deep enough. Don’t worry, that won’t be me today.

.

.

.

If you are just now rejoining me, welcome back. The reason for my waxing poetic a bit was twofold. One, obviously, to gush about my excitement. But more importantly, as way to point out that Doctor Who can be anything and go anywhere. The show doesn’t have to constrain itself to the past, and as gamers, we don’t either. Homebrew content, as it is normally called, is quite literally the foundation of our hobby. If you want to do a thing, do it. The rules are meant to be broken and having fun is more important than canon. If I want a creature from Paranormal Affairs Canada, I can adapt that. If I want the Doctor to crash onto a planet out of Starfinder’s Codex of Worlds, I can do it. (At this point I’m glad I’m not writing this at home, or I’d be mathing out how to adapt the Vesk into Silurians instead of writing this review.)

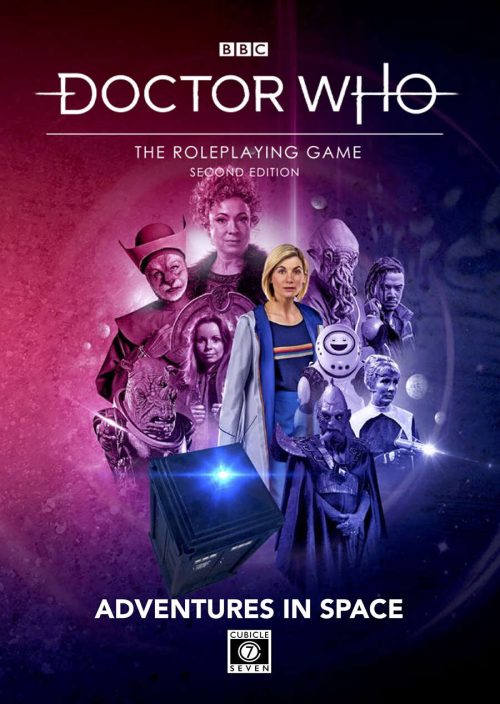

Adventures in Space is a sourcebook designed to give Gamemasters all of the specific tools they might need to create (or adapt) strange new worlds and strange new ways to travel to them. It is the companion book of the as-yet-unreleased Adventures in Time sourcebook. Despite focusing on the space side of the Doctor Who equation, space and time are inexorably linked and it can be argued that this is truer in Doctor Who than anywhere else. The second chapter of Adventures in Space talks about going on an adventure in space and is aptly titled: “Going on an Adventure in Space.” (I think I’m seeing a theme here.) The chapter looks at how locations in space can impact the sort of story a GM may tell. In the process, they also show just how intertwined Doctor Who, the show, is to each Doctor’s contemporary real world timeframe. The broad story strokes over the past 60 years are all fairly consistent and get touched on here. “Doctor Who-dunnit?” mysteries, humanity venturing into space, “The Rebel Doctor” stepping in to help the oppressed. These are all classic themes, but each story is heavily influenced by when it was written and when it was written about, no matter where in space they take place. Skaro is a planet with a much larger story than just the Daleks, and much of that story is influenced by the Cuban Missile Crisis, World War 2, and humanity’s first real world steps toward the stars. Satellite Five was used as commentary on the contemporary news cycle and later the pop culture dominance of gameshows and reality television. It was also used in other mediums, which aren’t actually mentioned, but reinforce how the same locations can serve different stories. Terra Alpha, and its leader Helen A, was a direct commentary on British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher. The list goes on. I’ve sort of worked my way backwards through this chapter since this is all summarized at the beginning of the chapter discussing using Space Adventures as Social Commentary. When you examine the stories from a social standpoint, you see it across the rest of the chapter regardless of how other themes are presented. That was a bit ramble, so to summarize: the chapter introduces and reinforces some of the most important aspects of an adventure… of the Doctor. (You thought I was going to say adventure in space again, didn’t you?)

Now that we all are on the same page about the sort of stories that can be told across the stars, Chapter 3 looks at how to get the players to those stories. Despite the title, Doctor Who The Roleplaying Game doesn’t specifically require a Doctor or a TARDIS, but if a group of Silurians (for example) want to adventure somewhere other than where they are, they will likely require some sort of Spaceship. One of the best aspects of the Vortex system that powers DWRPG is that everything sort of gets built in the same way. A player building a time machine is going to follow most of the same steps as they did in creating their character. A living, breathing, adventuring, character needs a few more details, but the process is still basically the same. Building a spaceship is functionally the same as building a time machine and building a character. First, you come up with a Concept for the ship, then a Focus within that concept. You add in Attributes and a Distinction or two. Finally, you come up with the Finishing Touches that bring the story of your ship to life.

Of course, the players aren’t the only life forms travelling the depths of space, so the chapter closes with a “Spaceship Recognition Guide.” The book points out that there are more types of ships than could possibly be included in this book. Indeed, Cubicle 7 could go the route of other publishers and crank out an entire book of just spaceships and stat blocks. However, in under 10 pages, they give a surprisingly broad selection of ships to serve as both inspiration and adversaries for the players. But remember, no matter how much you think you know: “No ship has a sign on the side saying to disable my engines, shoot me here.”

But what’s a ship with nowhere for it to go? Like a ship, the number of planets already in the Whoniverse is voluminous, but the number of planets that a Game Master (or Game Missy) can create is limitless. Creating a new planet is very much like creating a spaceship, which is very much like creating a time machine, which is very much like creating a character, and no that doesn’t mean you can be a living planet –Derek– now shut it before I feed your baby-faced character to the Goblin King. I mean, I suppose you technically could play one… but still no. Anywho, when you create a planet you’re still choosing a Concept, Focus, Attributes, Distinctions, and Finishing Touches. The major difference is that you aren’t assigning Attribute stats to the planet, but rather selecting a single Favoured Attribute that players will find the most useful on this planet. The other big thing to remember is that while you are creating a whole planet, your players will likely only interact with a small area of it at any given time. Unless you are super into world-building, there isn’t really a need to come up with an in depth encyclopedia on your world. In fact, leaving some things defined makes it easier to come back to that world in a later adventure and add whatever new details you may need. Even the next chapter, which looks at a ton of preexisting worlds, only dedicates two-page to each world that it covers.

As with most sourcebooks in this series, the book closes with an adventure, “The Terror of Elbonia-2,” and a handful of other Adventure Hooks to get a GM’s creative juices flowing. I won’t look at those today, as I’ve rambled on for quite long enough, I think.

The biggest question in any game is the same: “Do I need this book?” The answer is usually also a somewhat vague “depends.”

If you are a player, no. Unless you want to simply collect the books there is very little to Adventures in Space that your GM couldn’t walk you through when needed. In fact, if you have the Second Edition Core Rulebook you could probably even fake most of it. As a GM, the book is full of information and inspiration for you to pull from, and having a ready made adventure is always helpful. Knowing me, I’ll mostly pull this one off the shelf to cross reference information in other books. How do the cyber-ships in this book compare to this other cyber-ship in this other book? That sort of thing. If nothing else, the book is well thought out and I’ve enjoyed just reading it. Seriously, let’s normalize free-reading game books. You can start with Adventures in Space.